“Put your money where your mouth is,” we may tell someone who recommends big things without making any practical commitment. Suppose they respond by taking out from their pocket a bunch of currency notes and putting it in their mouth. Laughing at the absurdity, we would stop them: “Don’t take things so literally – use your intelligence.”

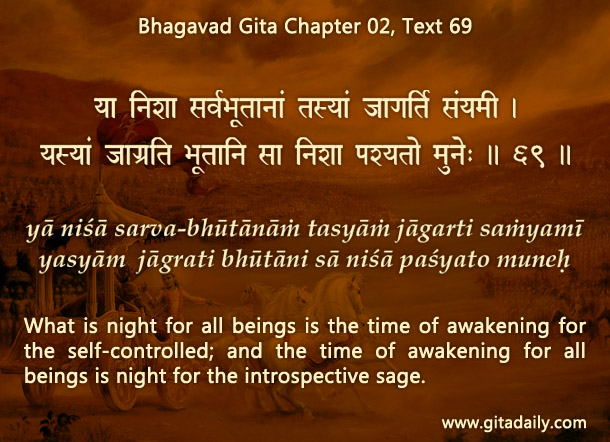

Non-literal usages are integral to living languages – and they feature especially in literary works such as poems. The Bhagavad-gita is, as its very name conveys, a poem. Accordingly, it features vivid figurative usages. Consider, for example, the Gita verse (02.69): That what is night for all living beings is day for the self-controlled, and vice versa. A literal reading makes no sense – unless the verse addresses two time zones twelve hours apart, and assumes that all self-controlled people live in one time zone and all common people in the other. But nothing in the verse’s context suggests that it is discussing geography; this Gita section (02.54-72) explains the characteristics of the spiritually realized.

A non-literal reading harmonizes much better with the context. If day refers figuratively to the arena of interest, and night to the arena of disinterest, the verse means: the sensual indulgence that fascinates general people doesn’t attract the self-controlled.

As a general principle, the Gita’s literary ornaments serve to enhance its message, not obscure it. So, non-literal interpretation shouldn’t be used to cloud that message, as happens when proponents of non-violence deem the Gita’s battlefield setting merely figurative. This setting drives home the Gita’s universality and urgency – if even a warrior on a battlefield found the Gita relevant, so too will we.

Overall, when we use our intelligence(18.63) to study the Gita devotionally (18.70), its import is revealed to us by Krishna’s grace.

To know more about this verse, please click on the image

Explanation of article:

Podcast:

Hare Krishna CCD,

Thank you for reminding us of the multiple level of understanding within the Gita. More one reads, more we awaken our understanding and relationship with Krishna.

It is very easy to take things literally than to use the intelligence