Now Krishna contrast it by telling that if one does practice renunciations then what will happen?

Bg 3.6

karmendriyāṇi saṁyamya

ya āste manasā smaran

indriyārthān vimūḍhātmā

mithyācāraḥ sa ucyate

Word for word:

karma–indriyāṇi — the five working sense organs; saṁyamya — controlling; yaḥ — anyone who; āste — remains;manasā — by the mind; smaran — thinking of; indriya–arthān — sense objects; vimūḍha — foolish; ātmā — soul;mithyā–ācāraḥ — pretender; saḥ — he; ucyate — is called.

Translation:

One who restrains the senses of action but whose mind dwells on sense objects certainly deludes himself and is called a pretender.

So, karmendriyāṇi saṁyamya, one should regulate the senses externally by practicing self-control, and ya āste manasā smaran, one should remember internally what one is thinking about.

Indriyārthān, remembering the objects of the senses,

Then what happens in this situation?

vimūḍhātmā, such a person becomes bewildered and deluded,

And what is Vimudha about the ātmā (soul)?

Actually, they believe they are making advancement, but in reality, they are not making any real progress.

mithyācāraḥ, such a person is deceiving themselves and others; this is hypocrisy.

Hypocrisy means to seek or accept the prestige and privileges that come with a position without fulfilling the responsibilities and sacrifices required for that position.

So, for example, if someone takes the position of a sannyasi, they should also fulfill the duties of that position. This includes sharing spiritual knowledge and giving up worldly pleasures, especially those related to desires for sense enjoyment.

In the Bhagavatam, it is mentioned that one should not become a guru unless they are capable of guiding their disciples effectively. This means providing training, education, and guidance that helps disciples transform their lives and progress toward liberation. If one takes on the role of a guru without being capable of offering such guidance, they are acting hypocritically.

This is what Krishna refers to as mithyācāraḥ, where one’s behavior contradicts their actual position. For instance, someone may claim to be a sannyasi but still engage in activities that go against the principles of sannyasa.

So, when karmendriyāṇi saṁyamya, one externally restrains their senses, but ya āste manasā smaran, internally dwells on those sense objects, that person is engaging in mithyācāraḥ.

So, we can say that we are also trying to follow the four regulative principles. However, there are times when we may also encounter undesirable thoughts. Does this imply that we become bewildered souls or offenders?

No, the outcome depends on how we handle these negative thoughts.

If a negative thought arises and we start embracing it, entertaining the notion of “Yes, I want more and more of this,” then we find ourselves in a precarious situation. Within our minds, there’s a mental gallery containing all the sense enjoyments we have experienced. If those experiences were immoral or contrary to devotional principles, then at times we might experience spontaneous, high-resolution flashbacks of those memories. We could find ourselves reliving those moments and thinking, “Oh, that was so pleasurable! I desire to relive that experience.”

In such circumstances, what should we do? The best approach is to consciously switch off that mental gallery and divert our thoughts elsewhere. We shouldn’t continue indulging in those thoughts. Moreover, it’s even more detrimental if we intentionally stir up those memories, musing, “How was that experience, again?”

In the context here, the phrase “āste manasā smaran” refers to deliberately nurturing memories of those sensory experiences, with the hope of enjoying them again in the future.

So, as a Sadhaka, we want to give up sense gratification, and these occasional thoughts are not hypocrisies.

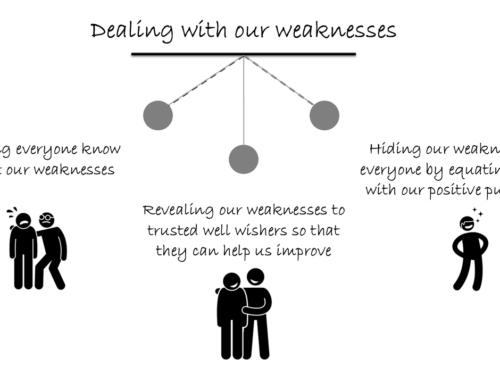

So, if we try to externally garb but don’t try for purification, that will not lead to perfection. However, if one adopts external garb and is far from trying for purification, continuing with past modes of thinking, then that is mityachara.

The best is when there is external change and internal change.

The second best is when there is external change and a sincere attempt at internal change.

The third is when there is external change, but there is no internal change at all.

The fourth is when there is external change, but there is a continuation of old ways with the garb of external change.

The difference between the third and fourth scenarios is that in the third, one has just adopted the externals, but in the fourth, one is using the external changes as a means for doing internal actions secretly. So, that is very unfortunate. Srila Prabhupada said that even if such a person has knowledge, such people must be called the greatest cheaters, even though they sometimes speak of philosophy. This is because they are making a show of being yogis while actually searching for objects of sense gratification. Such a pretender’s mind is always impure, and therefore, their show of yogic meditation has no value whatsoever. Thus, it is just a show and will not lead to any spiritual advancement.

So, in a broad sense, we may wonder if Krishna is condemning renunciation. We see that Srila Prabhupada himself took sanyas, and we have so many sanyasis and brahmacharis in our movement. Can we relate this to the Bhagavad Gita? What is Krishna telling here?

Actually, Krishna talks on multiple levels. In this section, Krishna is discussing Gyan yoga and karma yoga. Here, Krishna is not addressing Bhakti Yoga. Gyana Yoga involves inactivity, while Karma Yoga involves activity. Thus, Krishna is saying that inactivity and passive yogic meditation will not lead to any purification. Therefore, in this context, we are not discussing Bhakti at all. In Krishna Consciousness, whether a person is in a household or the renounced order of life, that person is actively practicing Bhakti. Krishna will address this later in the Bhagavad Gita.

For devotees, the principle is that the reason for taking sanyas is ‘Sarva Dharma Paritayja Mamekam Sharanam Vraja,’ as stated in 18.66, the conclusion of the Bhagavad Gita. For us, renunciation is not the primary focus; Bhakti is the practice. The renounced order is a facility for that sadhana. Thus, we adopt renunciation on the path of Bhakti to enhance our practice. It is not that we adopt renunciation because renunciation itself will lead to purification. No, renunciation is a tool for us to practice devotional service. This is what Chaitanya Mahaprabhu expressed: ‘Na Aham Vipra Na Narpati….’ He said, ‘I am not a Brahmachari, Vanaprastha, Sanyasi, or even a householder. I am the servant of the servant of Krishna.’ A devotee adopts renunciation for the practice of Bhakti, and it involves activity. In this context, Krishna is not discussing Bhakti; he is discussing Gyana yoga and Karma yoga. Gyana yoga involves inactivity. However, Gyana yoga is not sufficient; active engagement can be pursued through Karma Yoga or Bhakti Yoga. In ISKCON, even Brahmacharis and Sanyasis are actively engaged.”

Leave A Comment